Summary

The Vogtland/Northwest Bohemia region on the German-Czech border is a hotspot for earthquake swarms. In spring 2024, the first major earthquake swarm since 1897 developed in the Klingenthal-Kraslice region. Now, researchers led by Dr Pinar Büyükakpinar from the GFZ Helmholtz Centre for Geosciences have presented a detailed analysis of the more than 8,000 earthquakes. Their study has been published in the journal “Nature Communications Earth and Environment”. The evaluation of precise measurements and modelling of underlying processes show how the earthquakes developed over time and space. The researchers describe two phases of the earthquake swarm: a rapid, bidirectional spread and a slow, radial spread of seismic activity. These two phases correspond to two separate batches of fluids that entered an existing fault zone one after the other. In particular, the study identifies the influence of ascending CO2 and magmatic fluids as a major cause of the activation and underlines the central role of fluid overpressure in controlling swarm dynamics.

Background: Swarm earthquakes in the Vogtland region

Swarm earthquakes are a phenomenon in which up to thousands of earthquakes of similar, rather small to medium magnitude occur in a region over days, weeks or months. In fact, the term was coined in the German-Czech border region, which is a global hotspot for this type of earthquake – and therefore also a key region for their scientific research. Earthquake swarms are still a mystery, especially when it comes to the causes of their formation and progression.

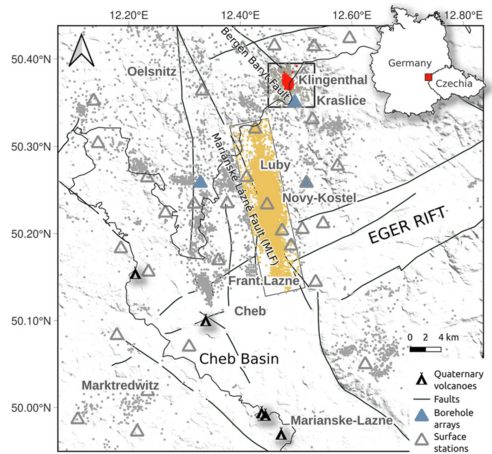

“The region around the Eger Rift, a fault zone of the European continental plate, offers an extraordinary natural laboratory with diverse magmatic activity, widespread carbon dioxide emissions and thermal waters rising to the surface, where we can study the interactions between tectonics, magmatism and fluid migration,” explains Dr Pinar Büyükakpinar, lead author of the current study and scientist in Section 2.1 “Physics of Earthquakes and Volcanoes” at the GFZ Helmholtz Centre for Geosciences. In particular, the researchers wanted to find out what role magma, CO2 and their interaction with water and rock play in triggering swarm earthquakes and deforming the upper crust.

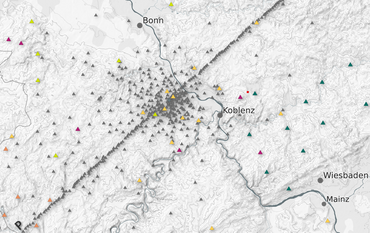

Densely instrumented region enables high-resolution measurements

Researchers have access to one of the densest seismic observation infrastructures in Europe. This includes four seismological and three fluid monitoring boreholes, several hundred metres deep, from the ICDP project “Drilling the Eger Rift”, several broadband seismic stations and the extensive seismic networks "WEBNET" and "Saxon" of the earthquake services in Czechia and Saxony. The data of the ICDP stations can be collected at a rate of 1,000 measurements per second. The GFZ researchers have also been active in this field for many years, most recently with the “ELISE” project, which involved setting up a uniquely dense network of 300 temporary measuring stations.

The 2024 earthquake swarm enables unique new investigations

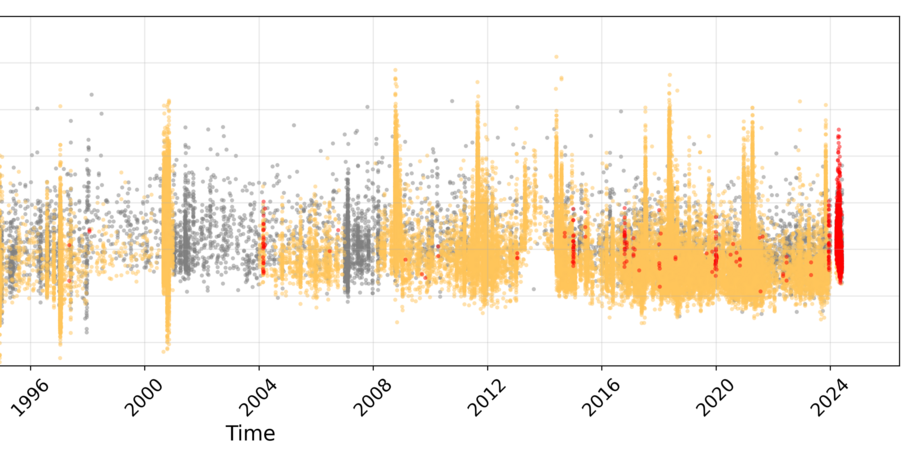

One of the most insightful “natural experiments” to date for understanding magmatic fluids in the Earth's crust was the 2024 earthquake swarm in the German-Czech border region. It began at the end of 2023 with a small group of microearthquakes, which developed over the following months into the first major earthquake swarm in the Klingenthal-Kraslice region since 1897, peaking between March and May 2024.

For the researchers, these quakes were a stroke of luck in the well-instrumented region, as Pinar Büyükakpinar points out: “On the one hand, the event coincided exactly with my CHASING project, funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) between 2023 and 2026, which aims to locate earthquake swarms with high precision and understand the mechanisms that lead to their formation. On the other hand, many of the measuring stations were only a few kilometres away from the active fault. This enabled us to record the swarm activity with exceptionally good resolution and detect more than 8,000 events down to a magnitude of –0.5 with a location uncertainty of less than 0.1 kilometres. This corresponds to a tenfold improvement in temporal and spatial resolution compared to conventional catalogues of earthquake events in the region.”

To evaluate and interpret the unique measurement data, the researchers also relied on machine learning methods and modelling approaches that had not previously been used for the region. In this way, the research team was able to replicate spatial migration patterns of seismic activity and thus explain the mechanisms underlying the various seismic phases that triggered the swarm in the first place.

Pinar Büyükakpinar conducted the research for the current study together with colleagues from the GFZ, the University of Potsdam, the Czech Academy of Sciences and the University of Leipzig.

Reconstruction of the earthquake swarm

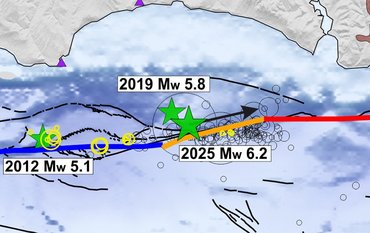

The Klingenthal-Kraslice swarm began in December 2023 about two kilometres north of the later swarm centre at a depth of between 10 and 11 kilometres – the greatest depth of all the earthquakes observed. After about three months, the quakes then migrated slightly southwards and to shallower depths. There, between March and June 2024, they occurred with a frequency not previously observed.

The cause of the swarm earthquakes is reservoirs of magmatic fluids deep beneath the region of north-western Bohemia/Vogtland, which form mainly in the upper mantle and at the boundary with the Earth's crust. If these areas become unstable, lighter melts and fluids can rise. If they encounter fracture zones in the Earth's crust and areas with varying rock strength, this can trigger earthquake swarms. Researchers suggest that this is also the trigger for the seismic activity in this case.

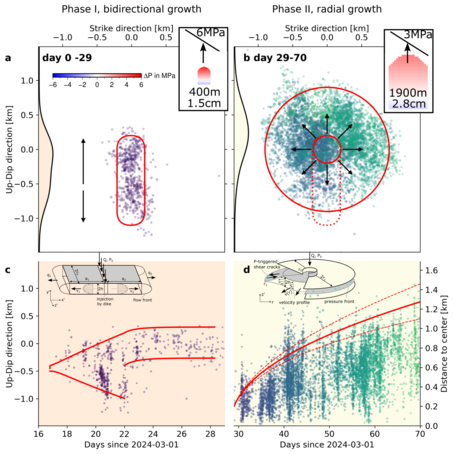

Two stages of development of the earthquake swarm

Further analysis revealed two different stages of development for the “main swarm”: a rapid and strongly asymmetrical expansion of seismic events in an elliptically elongated area from northwest to southeast in the first 5 days[UD1] , followed by a slower radial growth of the seismic front within a pronounced fault zone over a period of more than five weeks (see Figure 3). This correlation was achieved using a method that detects temporal changes in local seismic wave velocities (vp/vs) and thus identifies systematic changes in the apparent stress drop between phases 1 and 2.

To interpret these observations, the researchers used models that describe the penetration of fluids into rock and take into account parameters such as overpressure, viscosity and density of the fluid. They also relied on methods that are otherwise only used to study and model induced seismicity, i.e. seismicity caused artificially, for example by injecting fluids into rock.

According to these models, the Klingenthal swarm was generated by two separate batches of fluids that penetrated a previously unknown fault zone one after the other. In the first phase, a light, rather thin fluid with high buoyancy rose from below to the top over a period of about five days. The researchers estimate the volume to be around 320 cubic metres. The properties of this fluid indicate a high proportion of water and supercritical carbon dioxide.

In the second phase, the invading fluid spread more strongly to the side. This reduced the difference in density compared to the surrounding rock, indicating the inflow of melt or a melt brine. With 13,700 cubic metres, significantly more but heavier material penetrated, and the overpressure was lower. This favoured small shear fracture processes in the rock, which led to noticeable earthquakes. The observed properties are consistent with carbonate-rich melts.

“Our study illustrates how seismicity patterns can be used to reconstruct sequential injections of fluids into host rock and the properties of the fluids,” summarises Pinar Büyükakpinar. “Thus, we could identify an initial hydro-fracturing phase driven by CO₂-rich fluids, followed by hydro-shearing associated with denser magmatic or brine-rich fluids”.

Outlook: Further investigations and instrumentation

“Beyond the scientific findings, the Klingenthal-Kraslice swarm in 2024 has made it clear that more comprehensive, denser and cross-border monitoring is needed in north-western Bohemia and the Vogtland region,” says Prof. Dr Torsten Dahm, co-author of the study and head of GFZ Section 2.1 “Earthquake and Volcano Physics”.

One step in this direction is the EGER Large-N (ELISE) seismological experiment, which is coordinated by the GFZ. From August to November 2025, around 300 seismic stations were installed in an area measuring 100 × 100 kilometres, creating one of the largest passive seismic arrays ever set up in this area. Over the next 12 to 18 months, it is expected to contribute to an ever-improving understanding of swarm earthquakes in the region.

Original publication

Büyükakpınar, P., Dahm, T., Hainzl, S. et al. Modelling of earthquake swarms suggests magmatic fluids in the upper crust beneath the Eger Rift. Commun Earth Environ 7, 6 (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-025-03019-0

Upcoming publication, currently under review:

Büyükakpınar, P., Dahm, T., Isken, M., Doubravová, J., Křížová, D., van Laaten, M., et al. New Research Perspectives in Light of Dense Cross-Border Experiments in West Bohemia and Vogtland Regions. Manuscript under review.

Video

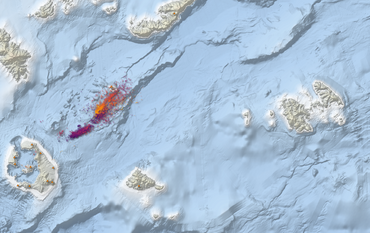

Spatio-temporal evolution of the 2024 Klingenthal-Kraslice earthquake swarm beneath the Eger Rift

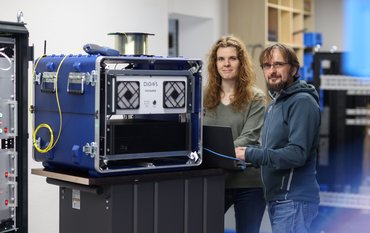

![[Translate to English:] Susanne Hemmleb (right) and her GEOFON colleague Peter Evans (both Section 2.4) hold the CoreTrus](/fileadmin/_processed_/0/a/csm_cert0677_CoreTrustSeal_Geofon-02_93ac53757f.jpeg)

![[Translate to English:] Group photo with 8 people in a seminar room in front of a screen.](/fileadmin/_processed_/2/1/csm_20251114_News_EU-Water-Resilience-Exchange_Kreibich_c-xx_db4e5be690.jpeg)

![[Translate to English:] Portrait photo, blurry background](/fileadmin/_processed_/a/2/csm_2025_11_06_JEAN_BRAUN_HE_Helmholtz_Portraits-23_2b5c35beee.jpeg)

![[Translate to English:] Excerpt from a map of the Phlegraean Fields near Naples, Italy: Left: Red dots mark smartphone sensors, yellow triangles mark fixed seismological stations. Right: The area is coloured in shades of yellow, red and purple according to the amplification of seismic waves.](/fileadmin/_processed_/3/b/csm_20251028_PM_Smartphone-Earthquake_Slider_12500fa0e6.jpeg)

![[Translate to English:] Green background, portrait of Heidi Kreibich](/fileadmin/_processed_/1/1/csm_20251023_Kreibich-Heidi-2025-Vollformat-green_web_-c-Michael-Bahlo_72946c7fe4.jpeg)

![[Translate to English:] semicircle depicting the future missions, graphics of the new satellites](/fileadmin/_processed_/3/d/csm_2025_10_08_Copernicus_Erweiterung_3f08a76a33.png)

![[Translate to English:] Portrait picture](/fileadmin/_processed_/f/4/csm_Magnall-Joseph-Kachel-c-privat_36e23315c3.jpeg)